Shovelhead

Although their main competitor in the US market –the Indian Motorcycle Company– had gone under in 1953 and left HD as the primary US manufacturer of big bore bikes, by the mid 1960s Harley Davidson was facing a crisis; after going public with its stock in 1965, they were facing heavy competition from overseas manufacturers.

Although their main competitor in the US market –the Indian Motorcycle Company– had gone under in 1953 and left HD as the primary US manufacturer of big bore bikes, by the mid 1960s Harley Davidson was facing a crisis; after going public with its stock in 1965, they were facing heavy competition from overseas manufacturers.

Honda had released their “Cub” series in 1958, blindsiding western motorcycle companies and virtually taking over the small displacement market (see The Japanese Rise to Domination). Once Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki joined the party and began exporting big bore machines Harley found themselves struggling to survive once again. Profits were in decline and the company’s financial picture looked bleak.

The Panhead had brought several improvements to Harley’s FL line, and their introduction of a 12v electric start system in 1965 had helped them stay above water in the heavy cruiser market. But as the bikes got heavier they required engines with more power than the Panhead could deliver, and in 1966 the company introduced the next evolution of their engine design.

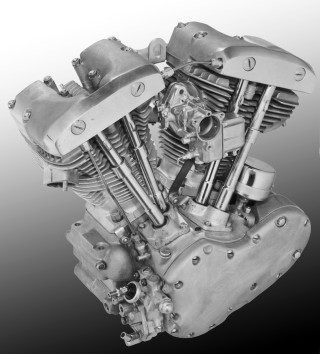

This new engine, like its predecessors, got its name from the shape of heads. Whereas the Panhead engine had valve covers resembling inverted kitchen pans, the new 74ci. (1208cc.) model had rocker boxes which resembled upside-down coal shovels. The name “Shovelhead” was adopted shortly after it was introduced.

This new engine, like its predecessors, got its name from the shape of heads. Whereas the Panhead engine had valve covers resembling inverted kitchen pans, the new 74ci. (1208cc.) model had rocker boxes which resembled upside-down coal shovels. The name “Shovelhead” was adopted shortly after it was introduced.

With the addition of an electric starter and the requisite larger battery, a fully dressed Electra-Glide happily provided some 800 pounds of resistance when it came time to move out of the garage. Harley-Davidson tried to counter that with deeper-breathing cylinder heads which theoretically resulted in a “10% increase in rated power”. In fact the weight of the engine itself had increased, so in practical application that 10% got knocked down a few points. That weight also affected the bike’s steering and could cause it to weave at top speeds.

With the addition of an electric starter and the requisite larger battery, a fully dressed Electra-Glide happily provided some 800 pounds of resistance when it came time to move out of the garage. Harley-Davidson tried to counter that with deeper-breathing cylinder heads which theoretically resulted in a “10% increase in rated power”. In fact the weight of the engine itself had increased, so in practical application that 10% got knocked down a few points. That weight also affected the bike’s steering and could cause it to weave at top speeds.

From 1966 through 1969 the shovelhead kept the panhead style lower end with generator bottoms that were often referred to as “slabside” shovels: several panhead owners upgraded their engines by simply swapping on the shovelhead cylinders and parts. From 1970 on the shovelheads used an alternator bottom often termed a “cone” shovel.

From 1966 through 1969 the shovelhead kept the panhead style lower end with generator bottoms that were often referred to as “slabside” shovels: several panhead owners upgraded their engines by simply swapping on the shovelhead cylinders and parts. From 1970 on the shovelheads used an alternator bottom often termed a “cone” shovel.

In January of 1969, Harley-Davidson merged with the American Machine and Foundry Company (AMF), who, despite their blue-collar-sounding moniker was primarily engaged in the production of consumer goods including model airplanes, lawn and garden equipment, Ben Hogan golf clubs and inflatable balls.

In January of 1969, Harley-Davidson merged with the American Machine and Foundry Company (AMF), who, despite their blue-collar-sounding moniker was primarily engaged in the production of consumer goods including model airplanes, lawn and garden equipment, Ben Hogan golf clubs and inflatable balls.

AMF supplied the money to keep Harley-Davidson afloat, but in an attempt to insure a return on its investment they stipulated an expansion of Harley’s poorly received line of smaller motorcycles. Harley had worked with Italian partner Aermacchi to produce the single-cylinder four-stroke 250-cc Sprint in the early 1960s, AMF turned to Aermacchi again for a string of even smaller two-stroke machines: the 6ci. (98cc) “Baja 100”. These were Harleys in name only, and they really harmed the company’s image more than they aided the bottom line. They failed miserably in comparison to cheaper and better designed Japanese imports, and as those comparisons went public many people applied them to the entire company. Although a die-hard fan base kept the Shovel alive, prospective new buyers lumped the FL line in with the junk bikes.

Despite problems with the early versions of the Shovelhead, the engine still provided a lot of power and Harley continued to improve it. Steel parts were gradually replaced with cast aluminum, reducing the engine weight which had been a primary complaint. In 1967 the Linkert carburetors were upgraded to Tillotson’s with accelerator pumps to provide better performance; from 1970 on Shovelheads were equipped with alternators, the new bottom end using a gear-drive unit. Mechanical breaker points and advance in the gear case replaced the external “timer” ignition.

Despite problems with the early versions of the Shovelhead, the engine still provided a lot of power and Harley continued to improve it. Steel parts were gradually replaced with cast aluminum, reducing the engine weight which had been a primary complaint. In 1967 the Linkert carburetors were upgraded to Tillotson’s with accelerator pumps to provide better performance; from 1970 on Shovelheads were equipped with alternators, the new bottom end using a gear-drive unit. Mechanical breaker points and advance in the gear case replaced the external “timer” ignition.

As the alternator and ignition were now located in the timing case, the case cover became cone-shaped. The inner and outer primary covers were redesigned for the alternator, which was mounted in the primary case. The cone-style lower end went on to be used on the later Evolution motors.

In 1971 a new FX Super-Glide was designed by Willie.G. Davidson, combining the lighter, thinner front-end of the XL Sportster with a Big-Twin frame and motor. At 560 pounds, it was 150 pounds lighter than an Electra Glide, and just 60 pounds heavier than a Sportster. In 1972 a front disc brake system was added, and in 1974 the Super-Glide was joined by the FXE, an electric-start version. Both models now had a one-piece gas tank instead of the FL Fat-Bob tanks. The FXE began out-selling the FX, soon becoming the most popular Harley Big-Twin.

In 1971 a new FX Super-Glide was designed by Willie.G. Davidson, combining the lighter, thinner front-end of the XL Sportster with a Big-Twin frame and motor. At 560 pounds, it was 150 pounds lighter than an Electra Glide, and just 60 pounds heavier than a Sportster. In 1972 a front disc brake system was added, and in 1974 the Super-Glide was joined by the FXE, an electric-start version. Both models now had a one-piece gas tank instead of the FL Fat-Bob tanks. The FXE began out-selling the FX, soon becoming the most popular Harley Big-Twin.

On top of the ongoing marketing issues forced on Harley-Davidson by their AMF partners, the US “Energy Crisis” of the 1970’s prompted new government regulations that limited motorcycles to a 90 mph. top end and severely constrained how much power the engine could deliver.

On top of the ongoing marketing issues forced on Harley-Davidson by their AMF partners, the US “Energy Crisis” of the 1970’s prompted new government regulations that limited motorcycles to a 90 mph. top end and severely constrained how much power the engine could deliver.

In 1977, the FXS Low Rider was introduced, sporting alloy wheels front and rear, twin disc-brakes in front, extended forks with a 32-degree rake, and a low 26-inch seat height. The Fat-Bob tanks returned, but with a new dashboard containing a speedo and tachometer. Unlike the Super Glide, the Low Rider was an instant hit, outselling other Harley-Davidson models in it’s first full year of production. All three FX models now had Fat-Bob tanks, with their own center divider.

Since 1966 the Shovelhead had displaced 74 cubic-inches, but in 1978 engine size was increased to 1340cc (80 cubic-inches) for Harley’s FL Big-Twin bikes. The cylinders were bored to 3.5″ and the stroke increased to 4.25″. Externally, the only difference between the two big-twins was the 80″ had one less fin on the cylinder. The larger engine was offered on the FX series in 1979.

Since 1966 the Shovelhead had displaced 74 cubic-inches, but in 1978 engine size was increased to 1340cc (80 cubic-inches) for Harley’s FL Big-Twin bikes. The cylinders were bored to 3.5″ and the stroke increased to 4.25″. Externally, the only difference between the two big-twins was the 80″ had one less fin on the cylinder. The larger engine was offered on the FX series in 1979.

Whereas the 74ci motor was designed to run on premium leaded fuel, the 80ci motor was designed to run on premium unleaded. Both the 74ci and 80ci engines were available for several years.Early Shovelhead motors also had a small-lip o-ring to seal the intake manifold to the cylinder head. Starting in mid-1978, the o-ring was replaced with a flat band with no lip. The base, kickstart-only FX was discontinued in 1979, and in 1980 a new belt-final drive on the FLT Tour-Glide gave quieter operation with no adjustment or lubrication needed. The new model also featured a redesigned frame and engine-mounting system, with the swing-arm bolting directly to the (also new) five-speed transmission. Minor improvements included a spin-on oil filter.

Further carburetor and weight improvements were implemented, but the engine never really developed into the powerplant that serious bikers wanted. In the first-year of Shovelheads (1966) there were four model designations: by production’s end in mid-1983, there were 16 models.

Still, the Shovelhead struggled to keep pace with other innovations that were sweeping the industry: components such as oil management systems were considered archaic when compared to other engines, and the machine fell out of favor.

Harley stopped producing the engine in 1984, and the Shovelhead was replaced by the Evolution engine that Harley still uses today.

Comments

Shovelhead — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>