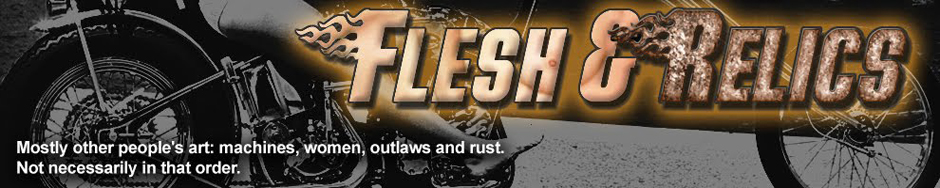

Although the origins of the zoot suit are unclear, the long jacket with wide lapels and high waisted, wide leg, pegged trousers became associated with the young urban African-American working classes in the 1930s. The style was made popular by some of America’s most prominent jazz musicians and performers (Dizzie Gillespie commonly wore zoot suits) and it resurfaced as a Chicano wardrobe in El Paso and Juarez, propelled into prominence by the Mexican comedian Germán Valdés (Tin-Tan) who sported the zoot suit and spoke in Caló in his films.

The term “Pachuco” (f.Pachuca) was coined for this new subculture; one theory claims that the term originated in El Paso, Texas, typically referred to as “Chuco town” or “El Chuco.” People originally moving from Los Angeles to El Paso would say they were going “pa’ El Chuco” (to Chuco town) and the term came back to LA when the flow of workers migrated back to industrialized city centers during the war. Pachucas also donned zoot suits, more often than not improvised men’s jackets with short skirts, fishnet stockings or bobby socks and piling their hair in pompadours. The pachucas especially broke out of cultural and gender norms, asserted their own distinct identity as Mexican American women. By 1930, East LA was home to the largest population of Mexican-Americans anywhere. Although the Great Depression saw immigration slow to a trickle, traqueros from El Paso brought their pachuco culture to LA. Although Hoover had forced the removal of nearly one million Mexican-Americans under the “Mexican Repatriation” act during the 1930’s, once 110,000 Japanese-Americans were interned in concentration camps in 1942 the US reversed its policy and invited Mexicans to return. As a result, East LA’s homogenization was effectively complete.

The paseo, still honored today in many small Mexican towns, is a tradition where young, unmarried villagers walking around the village’s central plaza. According to legend the “cruise” is merely an automotive extension of this ancient tradition; Pachuco culture was all about style, and style is pointless unless it has an audience. For East LA, Whittier Boulevard became the main paseo. Most Chicanos were poor farm workers without the money to afford a new vehicle, but as secondhand vehicles became more readily available the pachucos naturally began modding them. Unlike most “customizers” who were interested in speed, they were more interested in looks, class and style.Most of the cars cruising the barrios were Chevrolets; less expensive, easier to repair and more stylish compared to practical Fords. Rather than the fast looking “California rake,” these young pachucos would drop the back of the car for a sleek, mean look that turned everyone’s head.

|

| Leroy Semas’ 1937 Chevrolet Coupe |

Lowriders had first emerged in the barrios of Juarez in 1939 when young pachuco rebels lowered their rides by stuffing sand bags in the trunks of their cars, but as the style caught on they permanently shortened the springs all around by cutting the top few coils or heating them until they collapsed to a proper cruising height. Lowering blocks, z’ed frames and drop spindles soon came into play and the aim was to cruise as slowly as possible, “Low and Slow” (“Bajito y Suavecito”). Lowrider Magazine quotes former pachuco and United Farm Workers co-founder Cesar Chavez: “They were family cars, but we used to fix them up… In those days you went the opposite [of the hot rodders]–low in the back. We lowered the rear springs, had fender skirts, two side pipes. It was mostly cosmetic stuff in those days. You had to have two spotlights and two antennas, and a big red stop light in the back.The “alligator hood” looked great on models with hoods hinged down the center, like the ’39 Chevy. Originally, the hood would open up like wings, but this was converted to open from the front, like an alligator’s mouth.”

On August 2, 1942 the body of Jose Diaz was found in a southeast LA reservoir; the autopsy revealed that Díaz was intoxicated and death was the result of blunt head trauma consistent with being hit by a car. In a hysterical response (that would be repeated in the 1947 “Hollister Riot”) the media began a campaign calling for action against zoot suiters and for 10 days they promoted the idea that pachucos were goons, punks, anti-American, and a social threat. On August 10 the LA police rounded up 600 Latinos who were charged with suspicion of assault, armed robbery and various other charges, with 175 eventually being held for various crimes. Henry Leyvas and 24 members of what the media termed “the 38th Street gang” were arrested for the murder, but all convictions where later overturned for misconduct. By June 1943 simmering tensions between pachucos and white servicemen stationed in the industrial cities of Los Angeles, Detroit and Pittsburgh erupted in a series of violent episodes which became known as the “Zoot Suit Riots”, essentially a racial conflict; gangs of white servicemen invaded black and Hispanic neighborhoods, stopping streetcars and buses and entering theaters.

Pachucos were dragged out onto the street and assaulted: many had their clothes ripped off and their hair cut. Despite the brutality of these incidents most of the press and police remained sympathetic to the servicemen, frequently arresting victims rather than perpetrators of the violence. Military intervention and investigatory committees eventually put an end to the riots although many of the social injustices which lay behind them remained unchallenged and unchanged. What frightened many Southern Californians, however, was not just the pachucos’ rough and ready reputation: it was their ability to move through traditionally Anglo areas with ease.

“Being strangers to an urban environment, the first generation tended to respect the boundaries of the Mexican communities,” writes historian Carey McWilliams of the pachucos’ first lows. “But, the second generation was lured far beyond these boundaries into the downtown shopping districts, to the beaches and, above all, to the glamour of Hollywood. It was this generation of Mexicans, the pachuco generation, that first came to the general notice and attention of the Anglo-American population.” Perhaps predictably, after the war ended the zoot suit reentered the fashion scene as a mainstream style; by 1948 a slimmed-down version of the suit was being marketed by the American fashion industry as a new, postwar ‘bold look’ for the average (white) man. Stripped of its symbolism it soon fell out of fashion for the pachucos, but the lowrider endured.

|

| 1948 Chevy Fleetline Lowrider |

By the late 1950s and early ’60s, what we would now consider lowriders were finally hitting Whittier Boulevard in great numbers. Such fine rides wouldn’t appear overnight, however. California car culture and Mexican-American cultura would both develop and grow, each enriching the larger American culture with every passing decade.

|

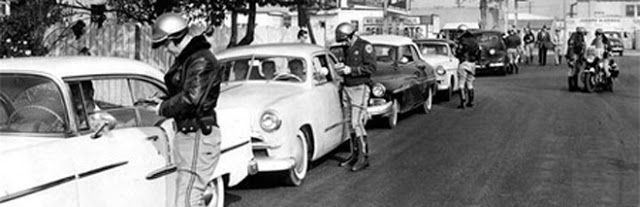

| Sobriety check on Whittier |

Beginning in the late 1940s, LA underwent a rapid transformation with the development of huge housing construction projects in the suburbs. This led to a greater dependence on cars, and that in turn led to the expansion of the freeway system. The importance of the car to a large percentage of LA’s population spurred custom shops, who now had a bonanza of cheap used cars available. Thousands of Mexican American veterans also either returned to the Los Angeles area or moved there in search of better jobs, and many of them had acquired advanced mechanical skills during their years of service in military vehicle motor pools, aircraft repair shops, and navy shipyards which they put to use customizing their own vehicles.

|

| “Hearbreaker” 1950 Chevy Hardtop |

In LA’s barrios, lowriders in the late 40s and early 50s preferred the 1939 Chevrolet Deluxe, the 1948 Fleetline, the 1950 Chevrolet hardtop, and the 1949 and 1950 Mercury; these models lent themselves to customizing. Small tires were used in order to lower the cruisers a few inches from the ground and were less expensive than the racing tires favored by hot rodders. Owners would typically visit junkyards in their vicinity to find spare car parts such as hubcaps, bumpers, grilles, and transmissions. Painting was one of the other essential skills that Mexican Americans had honed during their military service. While this was important in developing unique paint jobs, the use of thick Navy gray primer paint to cover up rust spots became very popular in San Diego, a major Navy port.

|

| Bo Huff’s 1950 Mercury Custom |

The automotive industry also attracted Mexican American families from all over the US; years later, when the automotive industry in Los Angeles fell on hard times, many of the temporary workers moved back to the cities and towns from which they had relocated taking with their new found customizing skills with them. This migration back to other locales gave a big boost to the spread of the SoCal lowrider subculture to other areas of the country. Although the term lowrider was still not commonly used in the early 1950s, much of the activity which was later associated with lowrider culture was already common.

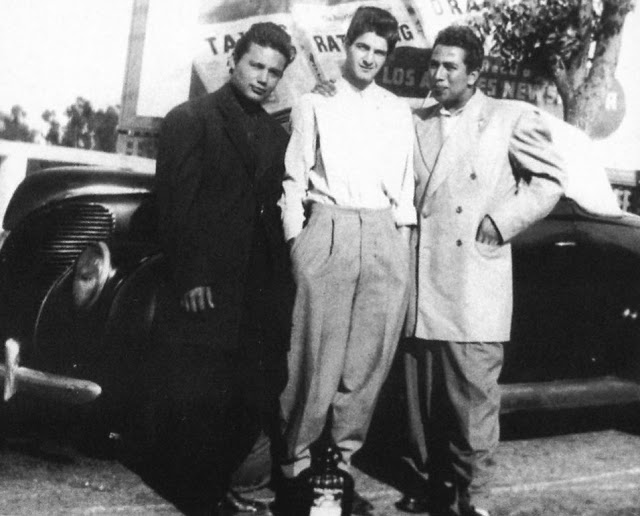

Groups of cruiser owners began to organize themselves into clubs with names like the Honey Drippers, the Pan Draggers and the Street Scruppers; congregating and cruising down the Miracle Mile in West LA, Olvera Street and especially Lincoln Park. Lowrider clubs would also drive longer distances to places like the rivers near Pico Rivera, Cabrillo Beach and Long Beach. Cruiser owners would use the streets and the places where they congregated to show off their cars, especially how low they were to the ground, the paint jobs, and decorative elements such as hubcaps, spotlights, grilles, and fenders. By the mid-1950s, a string of Clock Drive-Ins in LA communities such as Bellflower, Pasadena, and Long Beach prospered in part because some cruisers and other custom car owners needed locations to show off their paint jobs; the bright lights were ideal for highlighting the details. When the Clock Drive-In chain was acquired by A&W, cruisers started hanging out at Harvey’s Broiler and at other drive-ins in the Los Angeles area.

|

| Larry Watson’s paint shop on Artesia Boulevard in Bellflower, California |

|

| Classic TJ Tuck & Roll |

In the early 1950s, Larry Watson was in great demand as a painter of low and slow cruisers. He had his own car, a professionally painted Chevy that he took out cruising. Eddie Martinez, a top LA upholsterer found fame as car owners put greater emphasis on the interiors; across the border in Tijuana an upholstery industry started up to provide basic interior upgrades. But both California and Tijuana upholsterers soon learned to provide much more sophisticated (and expensive) options to cruisers. But by the late 1950s the cruisers once more started getting systematically harassed by law enforcement , especially traffic police. The new pretext for stopping a cruiser was that it was too low and causing damage to the street surface; in reality there was growing public concern and media coverage of the long lines of Mexican American owned vehicles cruising slowly up and down Whittier Boulevard in LA and the main streets of San Diego and Long Beach. Media coverage suggested that the cruisers were gangs of roving criminals threatening white residents. Although it is probably true that there were some gang members among the lowriders, the media grossly exaggerated it and pressure on politicians resulted in the California legislature passing a law in 1959 prohibiting the use of any vehicle with any part of it below the rim base. In 1959, a customizer named Ron Aguirre developed a way of bypassing the law with the use of hydraulic Pesco pumps and valves (scavenged from a surplus B-52 bomber) that allowed him to change ride height at the flick of a switch. The ’58 Chevy Impala featured an X-shaped frame that was perfectly suited for lowering and modification with hydraulics, and it became a hit.

|

| 1959 Impala with hydraulic kits |

Jesse Valadez’s “Gypsy Rose” first received national attention in 1974 when it was shown cruising down Whittier Boulevard during the opening credits of “Chico and the Man.” Although the original 1963 Impala was severely damaged by a rival club after taking virtually every show it was placed in, Valdez re-created it using a 1964 Impala. Adorned with about 150 roses, the interior features crushed pink velvet upholstery, chandeliers, a cocktail bar and space for wine bottles and a tape player. Gypsy Rose successfully competed in the show circuit for 12 years, was placed into storage, and re-emerged in 1996 to be a part of the “History Lane” display at the 20th anniversary Los Angeles Super Show.

|

| Jesse Valdez 1964 Impala “Gypsy Rose” |

Between 1960 and 1975, customizers refined GM X-frames, hydraulics, and airbrushing techniques to create the modern lowrider style. Heavier battery powered hydraulic systems from liftgate trucks soon replaced the old aircraft units, and mechanics soon learned that with enough power they could not only raise and lower the chassis but actually get it to hop off the ground. This quickly led to a new sport, and today’s hydraulics can get a competition car up to 6 feet in the air.

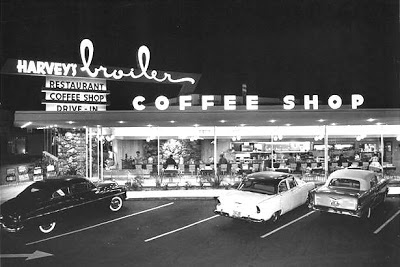

Lowriding in California and throughout the Southwest in general enjoyed a renaissance in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in large part due to the founding of Lowrider magazine in 1977 which covered club activities and shows across the United States along with highlighting custom cars. The appearance of lowriders and their cars in feature films and on television programs also sparked interest, although some of the portrayals of lowriders were decidedly negative. But while lowriding was booming elsewhere, by the mid-1980s it had begun to wane in in East LA. Lowrider clubs in other cities were able to form alliances to combat police harassment, but East Los Angeles suffered from too many rivalries and the antagonism that had existed between their clubs for years. After riots on Whittier Boulevard in June 1968 Los Angeles authorities prohibited any further cruising, and it would remain barricaded on weekends through most of the 1970’s. Lowriders moved to other routes like Santa Monica Beach and Crenshaw Boulevard but cruising was becoming difficult and most turned to the large car shows as an alternative to the old school paseo. Today the ’64 Chevy Impala is one of the most popular lowriders, along with other ’58-’66 Impalas to a lesser extent. 1978–88 GM G-bodies ( the Chevy Monte Carlo, Buick Regal, Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme and Pontiac Grand Prix) and their earlier relatives are usually seen as entry-level lowriders. Although heavy customization and flash paint remains popular, many lowriders pass for restored stock cars.

References:

Lowrider Magazine #1, Jan. 1977 (full scan by Iowahawk)

Lowrider Magazine (Official Website)

The Lowrider History by Rebecca M. Cuevas De Caissie (BellaOnline)

Lowriders in Chicano Culture: From Low to Slow to Show by Charles M. Tatum

Street Low magazine

Alfonso Acuna / Barrio Girls Magazine