An Incident at Hollister: Facts, Fiction and the Birth of the American Outlaw Biker Culture.

|

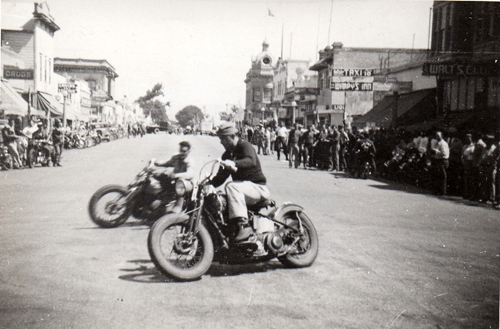

| Downtown Hollister, CA. |

History of the AMA

In 1903 the New York Motorcycle Club formed The Federation of American Motorcyclists (FAM),

stating that: “Its objects shall be to encourage the use of motorcycles and to promote the general

interests of motorcycling; to ascertain, defend and protect the rights of motorcyclists; to facilitate

touring; to assist in the good roads movement; and to advise and assist in the regulation of motorcycle

racing and other competition in which motorcycles engage.”

For the next 16 years the FAM developed competition rules and rider classifications, and attempted to

resolve restrictive motorcycle ordinances in cities like Chicago and Tacoma, Washington, but World War

I drained potential members and the organization went out of business in 1919. In the mean time

several trade associations also developed among American motorcycle manufacturers, specifically the

Motorcycle and Allied Trades Association (M&ATA) which was founded in 1908. When failing

membership rolls eventually ended the FAM, the M&ATA began registering clubs and supporting

motorcycle activities. In 1919 it began a rider registration and by 1920 was supporting annual “Gypsy

Tours”, gatherings in individual states where motorcycle riders would meet to compete in flat track

races, hill climbs, obstacle courses and other events. In May 1924 the directors of the M&ATA

proposed to create the “American Motorcycle Association” to control the rider’s registration and

activities, issue sanctions for national events, and serve motorcycle industry members. The first

national event operated under an AMA sanction was most likely the second annual National Six Days

Trial, a 1,400-mile endurance run that started and finished in Cleveland.

By 1925, 212 individual Gypsy Tours were held but like nearly all organized motorcycle events they

were suspended during World War II: when the war ended in 1945 America found itself with an

abundance of surplus motorcycles and plenty of restless young men straight from the battlefields,

trying to find a place in a now unfamiliar society.

According to The Outlaw Biker by Digits:

“The post war supply of cheap motorcycles not only presented the restless men an avenue for their youthful energy, the rough and powerful ride from the Harley Davidson or Indian motorcycles of the day gave that edge to life these men had known in war but was hard to find in suburban America. Many chose the life of the road with like minded individuals who liked to ride hard and party harder rather than settle in the routine of a nine to five job, mortgages and the stresses of raising a family. Just as the man either side of them in war was closer than any brother, their fellow riders became family. Since these were men that were used to serving under a symbol, wearing patches of who they were and what they represented, it wasn’t long before the different groups became more organized and gave themselves an identity, something surely lacking for many. Two of the first such organizations were the Pissed Off Bastards and the Booze Fighters.”

The AMA was quick to recognize these groups and designated them as “Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs” to signify that they didn’t adhere to its standards, blocking them from competing in their events. The official AMA website states that:

“…Through the 1950s, though, a small segment of outlaw motorcyclists began to give the Gypsy Tours a bad name. In 1957, the AMA changed direction and gave these events a new identity, along with a new name–AMA Tours.”

In fact that “bad name” started in 1947, specifically in the small town of Hollister in California’s San Benito county.

The Hollister “Riot”

In 1947 the AMA scheduled a California Gypsy Tour for the 4th of July weekend in Hollister, California, an otherwise quiet farming town of about 4,500. The gently rolling farmland surrounding the community was well-suited to motorcycle riding; there were facilities for scrambles, hillclimbs and dirt-track racing at Bolado Park (about 10 miles away) and at Memorial Park, on the outskirts of town.

Hollister had previously been the site of popular AMA races and as attendances grew they “became as important to Hollister as the livestock fair or the rodeo.”

But this year was different. Along with the Salinas Ramblers MC and the Hollister Veterans Memorial Park Association the AMA had arranged a $1,200 purse for their flattrack race, the equivalent of a small fortune at the time. Beginning Friday morning thousands of motorcyclists poured into town, coming down from San Francisco, up from L.A. and San Diego and from as far away as Florida and Connecticut.

By Saturday the event was estimated to have brought in as many as 3,000 bikers, and San Benito Street was choked with motorcycles. “Eager to prevent the locals from straying into the crowd”, the seven-man Hollister Police Department set up road blocks at either end of the main street but no one was prepared for that kind of turnout.

According to Jim Cameron of Boozefighters MC:

“… back then, the AMA organized these ‘Gypsy Tours’. One was going up to Hollister on the

Independence Day weekend. That sounded good, so a bunch of us decided to ride up there. We left

L.A. Thursday night, and rode through the night. I think my Scout only went about 55 miles an hour, so it took quite a while. I think we rode until we were exhausted, and stopped to sleep for a few hours in King City. It was about 6 a.m. when I woke up. It was pretty cold, and when the liquor store opened, I bought a bottle, which I drank to try to get warm. Then I rode on in Hollister.

“It was about 8:30 a.m. on Friday morning when I arrived there. I was riding up the street, and I see

this guy, another Boozefighter come out of a bar, and he yells ‘Come on in!’. So I rode my bike right

into the bar. The owner was there, and he didn’t seem to mind at all. He could see I was already pretty

drunk, so he wanted to take my keys; he didn’t think I should go riding in my condition. The Indian

didn’t need a key to start it, but I left it there in the bar the whole weekend. I don’t think there were

more than maybe 7 of us from the L.A. Boozefighters there. There were some guys from the ‘Frisco

Boozefighters, too. One of our guys had a ’36 Cadillac. He used that to tow up our trailer. We had a

trailer with maybe fifteen or sixteen bunks in it; stacked three high on both sides. Basically, we’d drink

and party until we crapped out, then we’d go in there and sleep it off.”

“They claimed there were about 3,000 guys there. I think most of them went out to the dirt track races

outside of town, but we didn’t. We were having fun right there. The street was lined with motorcycles,

and the cops had blocked it off. Basically, guys were just showing off; drag racing, doing power circles, seeing how many people they could put on one bike, and we were just watching and laughing.”

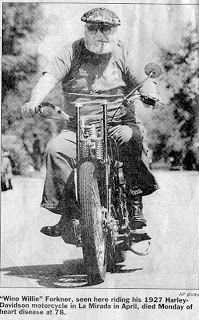

“…there were a couple of cops there, but they were playing it cool. Basically, they didn’t arrest

anybody unless they did something to deserve it. The one Boozefighter I can think of that got arrested

was a ‘Frisco guy. Some of them had come down in a Model T Ford. It was overheating, and while they were driving down the street, he was trying to piss into the radiator. Anyway, they arrested him, and Wino Willie went down to try to get him out; he was pretty drunk at the time, so they arrested him, too. But they let them both out after a few hours. Around Saturday night I started to sober up. After all, I had to ride home on Sunday. I guess I, got my bike out of the bar and headed home at about 4 p.m. on Sunday. It definitely wasn’t as big a deal as the papers made it out to be.”

By Thursday all the camping areas and boarding houses were packed, and bikers were forced to sleep on sidewalks and in the parks. By most accounts the “trouble” started on Saturday night when the AMA sponsored dinner and dance was full: the majority were turned away at the door so the crowd headed for San Benito St. where all the bars and restaurants were already overwhelmed.

Still, the crowd was pretty much under control. Marylou Williams and her husband owned a drug store on Hollister’s main street:

“My husband and I owned the Hollister Pharmacy, which was right next door to Johnny’s Bar, on Main Street. We went upstairs in the Elks Building, to watch the goings-on in the street. I remember that the sidewalks were so crowded that we had to squeeze right along the wall of the building. Up on the second floor of the Elks Building, they had some small balconies. They were too small to step out onto, but you could lean out and get a good view of the street. I brought my kids along; I had two daughters. They were about 8 and 4 at the time. It never occurred to me to be worried about their safety. We saw them riding up and down the street, but that was about all; when the rodeo was in town, the cowboys were as bad.”

At first the bars welcomed the bikers with open arms, but the police requested they close two hours

earlier than normal. There was a half-hearted attempt to comply with orders to stop serving beer, on the theory that the bikers probably couldn’t afford hard liquor. But the party had begun- most of the bikers ignored the sanctioned races going on at Memorial Park, electing to hold their own drunken drags, wheelie and burnout displays and impromptu relay races right on the main street.

|

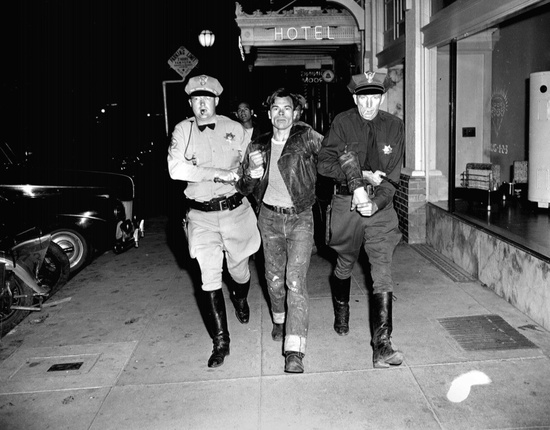

| In the midst of a “riot” police struggle to gain control. Of one guy. Note the lack of carnage. |

On Sunday however things escalated as a troop of California Highway Patrol officers arrived in a blatant show of force, threatening the now exhausted and hungover crowds with tear gas. It’s generally assumed that the local police had simply called them in for backup in case the crowds took too long to disperse, but suddenly the festivities took a much darker overtone. Nonetheless, the bikers scattered without any serious confrontation- nursing some hangovers and returning to their jobs. But the fallout was just beginning.

On Sunday however things escalated as a troop of California Highway Patrol officers arrived in a blatant show of force, threatening the now exhausted and hungover crowds with tear gas. It’s generally assumed that the local police had simply called them in for backup in case the crowds took too long to disperse, but suddenly the festivities took a much darker overtone. Nonetheless, the bikers scattered without any serious confrontation- nursing some hangovers and returning to their jobs. But the fallout was just beginning.

Generally this was a remarkable event, but as much for what didn’t happen as for the party itself. In total, 50-60 bikers were treated for injuries at the local hospital, including the injuries from sanctioned events such as dirttrack races and hillclimbs which were grueling enough. About the same number were arrested and charged with misdemeanors: public drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and reckless driving.

Most were held for only a few hours. No one was killed or raped; there was no notable destruction of property, no arson or looting; in fact no locals suffered any harm at all and the town itself reaped a huge economic boon.

So how did a seemingly controlled (albeit larger than expected) event suddenly find itself thrust into the living rooms of mainstream America billed as an uncontrolled riot?

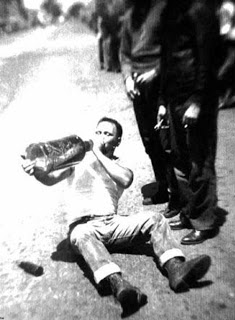

The local Hollister newspaper The Free Lance naturally published the first reports on the weekend starting

with a fairly mundane column reporting “49 arrests netting $2000 in fines” alongside a larger column

reporting on the outcomes of the races themselves. But as word of the event spread they began

fielding telephone calls from newspapers all across the country and by Monday they had changed their

tune and were reporting on “The Battle of Hollister”. Shit really hit the fan when a San Francisco

Chronicle reporter, C.I. Dourghty picked up on the story and travelled down with photographer Barney

Peterson in tow. Finding little in the way of a real story, they began staging photographs. While they

didn’t actually lie, the forthcoming stories carried sensational headlines like “Havoc in Hollister”, and

“Riots… Cyclists Take Over Town”. The AMA’s public-relations nightmare got even worse two weeks

later when the July 21, 1947, issue of Life magazine ran a full page copy of Peterson’s staged drunkard

swaying atop a Harley with a beer in each hand, over the headline “Cyclists’ Holiday, He and friends

terrorize a town,” and the following caption:

“On the Fourth of July weekend 4,000 members of a motorcycle club roared into Hollister, California, for a three-day convention. They quickly tired of ordinary motorcycle thrills and turned to more exciting stunts. Racing their vehicles down the main street and through traffic lights, they rammed into restaurants and bars, breaking furniture and mirrors. Some rested by the curb. Others hardly paused. Police arrested many for drunkenness and indecent exposure but could not restore order. Finally, after two days, the cyclists left with a brazen explanation. “We like to show off. It’s just a lot of fun.” But Hollister’s police chief took a different view. Wailed he, “It’s just one hell of a mess.”

When the media and consequently the American public reacted to the sensationalist side of the story,the AMA allegedly tried to distance itself by claiming that:

“The trouble was caused by the one percent deviant that tarnishes the public image of both motorcycles and motorcyclists “*

It is perhaps relevant to note here that of the estimated 3,000-plus bikers that showed up, by some accounts only about 10 – 20% were AMA registered riders: blaming only 1% of the crowd could in itself be considered a testimony to the relative lack of trouble over the weekend.

But those who had been branded as outlaws weren’t exactly interested in begging for sympathy or understanding; the guys who had actually been there weren’t buying into the media hype, they had no patience for the bullshit that subsequently got tossed around, and the AMA statement came down not as an insult but as a badge of honor.

The Boozefighters MC, Market Street Commandos MC and Pissed Off Bastards of Bloomington MC had already borne the brunt of the AMA’s wrath for years, and according to an interview with Wino Willie Forkner, Boozefighters responded by simply developing an offshoot club (the Yellowjackets MC) which got a separate AMA sanction for racing (Boozefighters MC claims to have never been a 1% club). The POBOB on the other hand reportedly developed a split, with Otto Friedli leaving in 1948 to form his own club in Fontana, CA., known as the Hell’s Angels. (in 1954 the Market Street Commandos merged with the Fontana club, founding the San Francisco chapter of Hell’s Angels MC.)

There is some dispute about the actual origins of the club: Friedli himself later became a fundamentalist Christian and denied that he started the Hell’s Angels, and much of what’s been written about the founding is third or fourth hand accounts or simply crap pieced together by various “legal experts” pushing their own agendas: but in his book Hell’s Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club Sonny Barger quotes Vic Bettencourt, who seems to back up Wino Willie’s version:

“… the first Hell’s Angels motorcycle club was formed around 1948 in Berdoo, an off-shoot from a renegade group called the Pissed Off Bastards out of Fontana, California. It was right after the Hollister incident. WWII vets from Berdoo—who belonged to the Pissed Off Bastards—used to roar by on their bikes. People would look up and say, “There goes one of those Hell’s Angels.”

Regardless of the specifics of their origins, the Hell’s Angels MC were most likely one of the first clubs

to adopt the 1% diamond patch in 1948 or 1949.

Today the patch is an universal symbol of the “outlaw” biker: people to whom the motorcycle and the

unique brotherhood -associated with a lifestyle outside of the normal boundaries of society- mean much

more than an occasional dirt track meet or Sunday ride.

* The AMA has often denied issuing this statement. To be fair, there do not seem to be any recorded instances of it detailing the speaker or the exact date and time of the press conference where it was allegedly uttered, however the author also finds it unlikely that such a statement should be fabricated considering that at the time most of the “outlaws” involved were actively seeking rights to compete in AMA sponsored events.

References:

The real “Wild Ones’ The 1947 Hollister Motorcycle Riot

The Outlaw Biker by Digits

The History Of The AMA

Cycle Guide Magazine: The Hollister Invasion: The Shot Seen ‘Round The World

The ‘One-Percenters’ by Jordan Smith

History of the Boozefighters MC

The History of the Hells Angels: 60 Years of Raising Hell The Myriad Mysteries, Legends and Attitudes Toward the Outlaw Motorcyclists by Greg Brian

Hell’s Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club; Harper Paperbacks (October 2, 2001)

Interesting stuff again, and some nice bikes with die for paint jobs.