In World War I, most airplanes did not have an enclosed cockpit and pilots had to wear something that would keep them sufficiently warm. The U.S. Army officially established the Aviation Clothing Board in September 1917 and began distributing heavy-duty leather flight jackets with high wraparound collars, zipper closures with wind flaps, snug cuffs and waists, and sometimes fringed and lined with fur.

The Type A-2 flying jacket was standardized by the U.S. Army Air Corps as the successor to the Type A-1 flying jacket adopted in 1927. The Type Designation Sheet lists the dates for Service Test as September 20, 1930, and Standardized on May 9, 1931. The military specification number for Type A-2 is 94-3040.

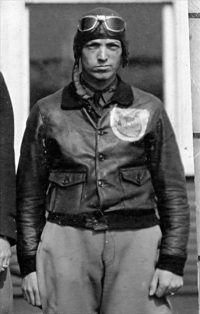

The U.S. Army Air Forces Class 13 Catalog describes the jacket’s construction as “seal brown horsehide leather, knitted wrists and waistband.” Although the actual design would vary slightly depending on the manufacturer, and even among contracts within a single manufacturer, all A-2 jackets had several distinguishing characteristics: a snap-flap patch pocket on either side without hand warmer compartments (hands in pockets were considered unfit for a military bearing), a shirt-style snap-down collar, shoulder straps, knit cuffs and waistband, a back constructed from a single piece of leather to limit stress on the garment, and a lightweight silk or cotton inner lining with a leather hang strap (not a loop) and military spec tag attached just below the back collar.

Most pre-war and wartime A-2s were constructed of horsehide, which was either vegetable- or chrome-tanned. Some original A-2’s were made from goatskin (as was the Navy G-1 jacket), and others possibly from cowhide. Wartime-issued A-2 jackets appeared in a wide range of color tones, although all are based on two distinct colors: Seal (dark brown to almost black) and Russet (pale red-brown to medium brown). Early A-2’s had linings made from silk, although the lining changed to cotton later on. A letter from the Materiel Division of Wright Field, dated 7 January 1939, states that the use of silk in flying jackets had been discontinued “as its procurement was found not to be feasible.”

The A-2 was one of the early articles of clothing designed expressly to use a zipper.

Army Air Forces officers were awarded the A-2 jacket upon completion of basic flight training, and always before graduating to advanced training. No standard system of distribution was used, though generally they lined up in front of boxes containing jackets of various sizes and which were distributed by the base quartermaster. A-2s were exclusive to commissioned officers until early in World War II, when they were also issued to enlisted aircrews. But as the A-2’s popularity grew, so did the demand for it; a few celebrated nonflying officers like Gens. MacArthur and Patton and Maj. Glenn Miller managed to procured and wear them. A “cottage industry” soon appeared making A-2-style jackets for GI’s who otherwise couldn’t get one, and they experienced a boon when the Army stopped purchasing new leather jackets in mid-1943 and began distributing less desirable cloth jackets and airmen found themselves unable to replace A-2’s they had lost or damaged.

The jacket was a treasured item to the airman, and was worn with as much pride as his wings. Fighter pilots, who often had heated cockpits, could wear the A-2 into combat more easily. Some jackets had a map of the mission area sewn into the lining, which theoretically could be used for navigation if shot down. Jackets from the China Burma India Theater, and more famously those of the Flying Tigers had a “Blood chit” sewn on the lining or outer back, which promised rewards to civilians who aided a downed airman. In certain ETO units a prerogative of the fighter ace was a red satin lining which was added on confirmation of his fifth aerial kill.

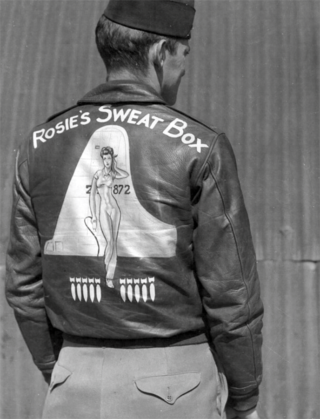

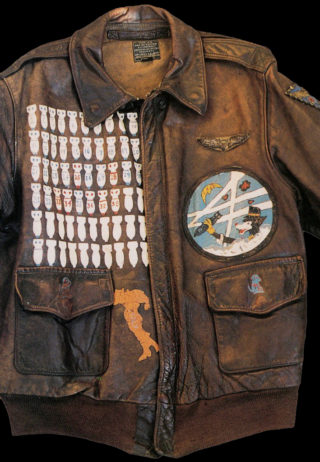

As airmen progressed through various duty stations they often added and removed squadron patches and rank marks, and most jackets ended up with numerous stitch marks as patches were removed and replaced when the owner changed units; unlike Navy aviators who often wore the patches of every squadron they had flown with, AAF personnel could only display the patch of their current assignment. Bomber crews often added small bombs to the right front of their jackets indicating the number of missions they had flown.

As airmen progressed through various duty stations they often added and removed squadron patches and rank marks, and most jackets ended up with numerous stitch marks as patches were removed and replaced when the owner changed units; unlike Navy aviators who often wore the patches of every squadron they had flown with, AAF personnel could only display the patch of their current assignment. Bomber crews often added small bombs to the right front of their jackets indicating the number of missions they had flown.

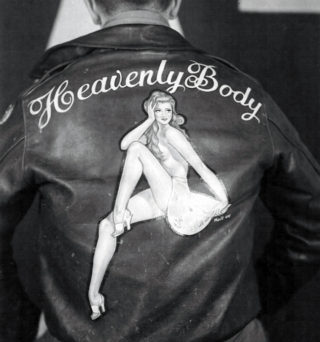

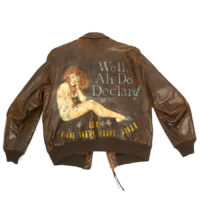

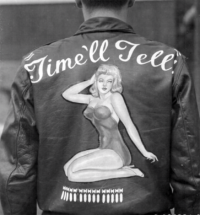

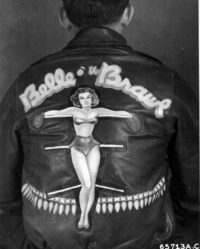

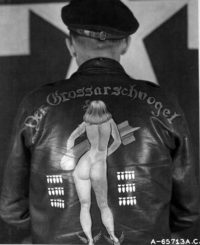

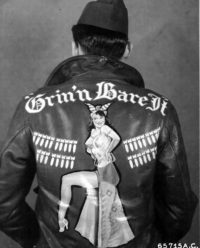

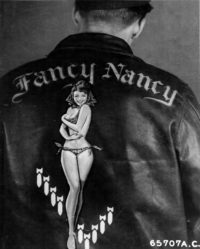

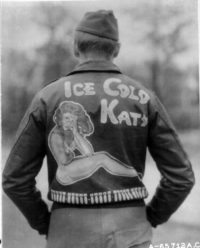

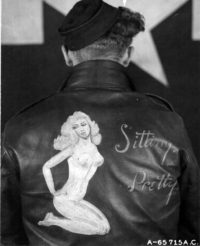

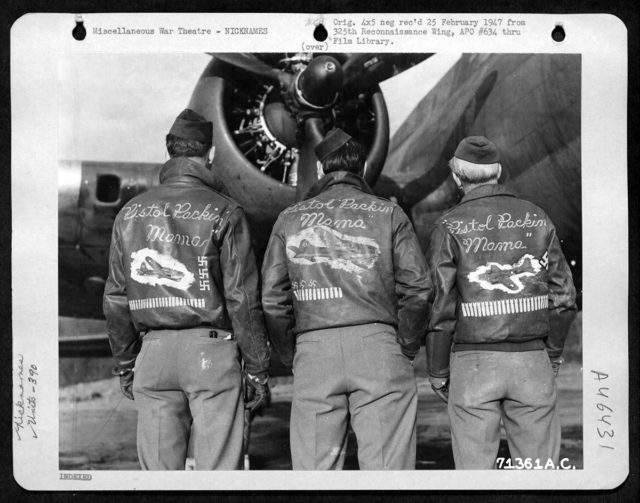

Although the concept of customization was (and is) generally frowned upon in the U.S. military, American soldiers have always held on to their individuality in some manner. World War II was a situation in which everybody enlisted, and many officers were only strict about the regulations that mattered. John Conway, co-author of American Flight Jackets and Art of the Flight Jacket explains: “… when you were up there in a plane, you’d get shot at, and you couldn’t call field artillery to support you. You had no ambulance, no medic. The officers figured, ‘Well, if this guy wants to paint a naked lady on the back of the jacket, what good is it to try to stop him? He could be dead tomorrow morning.’ The main objective was winning the war, not enforcing minor regulations and rules.”

The A-2 quickly became a canvas for teenage flyers to express their individuality, having the backs painted to included a plane’s nickname and nose art. On the bawdiest of these scantily clad babes gleefully ride phallic bombs; on others, popular cartoon characters charge forward, and some jackets depict caricatures of Native Americans or Pacific Islanders. Others show swastikas or Japanese rising sun emblems representing enemy aircraft downed.

After the war, many airmen returned home wearing their flight jackets, which by then had become almost a second skin. But Conway again notes that: “…When you’re a teenager and you’re 3,000 miles from home, having a naked lady painted on the back of your jacket is not that big a deal. But you wouldn’t want your mom to see it.” Nonetheless, as thousands of young military veterans began to pick up surplus Harley Davidson and Indian motorcycles back home, the concept found a new life in the burgeoning biker culture of the 1950’s. So-called “Outlaw Clubs” replaced the personalized crew emblems with motorcycle club patches (see An Incident at Hollister: Facts, Fiction and the Birth of the American Outlaw Biker Culture).

After the war, many airmen returned home wearing their flight jackets, which by then had become almost a second skin. But Conway again notes that: “…When you’re a teenager and you’re 3,000 miles from home, having a naked lady painted on the back of your jacket is not that big a deal. But you wouldn’t want your mom to see it.” Nonetheless, as thousands of young military veterans began to pick up surplus Harley Davidson and Indian motorcycles back home, the concept found a new life in the burgeoning biker culture of the 1950’s. So-called “Outlaw Clubs” replaced the personalized crew emblems with motorcycle club patches (see An Incident at Hollister: Facts, Fiction and the Birth of the American Outlaw Biker Culture).

In 1943, the A-2 jacket was discontinued as an official Army Air Forces garment due to the expense of production. It was superseded by the B-10 and B-15 jackets, which became the new Air Force standard. Although the Type A-2 jacket was only in production from 1931 to 1943, it was soon considered an American classic.

Due to continuing demand, the Type A-2 Jacket was reintroduced by the US Air Force in 1988, though with some major modifications: they were made exclusively from goat skin, the cut was much wider, and they now utilizedsynthetic fibers instead of wool, cotton or silk. After another redesign a few years later side pockets were added, the patch pockets got bigger and were re-positioned towards the middle.

Original wartime issued A-2 jackets are rare but not unavailable, and often sell at auctions with wearable examples generally running $1,000 and up. The National Museum of the United States Air Force has a collection of original A-2 jackets, most donated by the families of Air Force pilots. No fewer than fifty are on display at any time throughout the Museum, including many historic jackets such as Brig. Gen. James Stewart’s A-2 (a Rough Wear contract 42-1401), an A-2 from the AVG “Flying Tigers,” and another worn by one of the few U.S. pilots to get airborne during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Read More:

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys; Lisa Hix, Collectors Weekly

History of Leather Bomber Jacket: AmericanMystique.com