Albert G. Crocker was born in Maine in 1882. Little is known of his youth; he attended The Armour Institute at Chicago’s Northwestern University (now the Illinois Institute of Technology), graduating with a degree in engineering. His first job after graduation was with the Aurora Automatic Machine Company, a machine shop that had been established in 1886 to provide forging and castings for bicycle manufacturers.

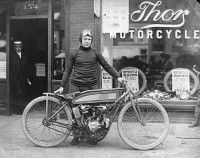

In the fall of 1901 Oscar Hedstrom and George Hendee approached the Aurora factory with prototypes of what would become the first Indian motorcycles (see “The Indian Motocycle Company: An American Icon”); in the next year Aurora made 137 engines for Indian, and by the following year they had begun marketing their own line of motorcycle engines and components in kit forms under the Thor Moto Cycle and Bicycle Company.

In 1908, after the Indian Moto-Cycle Company built their own in-house foundry, Thor began offering complete machines: ending their prior agreement with Indian which had stipulated that Aurora would not build motorcycles to compete directly with them while under contract for engines and parts.

Al Crocker was working in the style and design department of the Thor motorcycle division and had not only been a key part of the engineering team; he had also become a serious and successful competition racer, and often represented the company in endurance runs. During the 1907-09 seasons he had taken several competitive events on Thor V-twin powered machines, but he had developed a close friendship with Hendee and Hedstrom and in 1909 Crocker left Thor to join Indian. He was sent to San Francisco to handle the parts department in the factory headed by “Hop” Hopkins.

Al Crocker was working in the style and design department of the Thor motorcycle division and had not only been a key part of the engineering team; he had also become a serious and successful competition racer, and often represented the company in endurance runs. During the 1907-09 seasons he had taken several competitive events on Thor V-twin powered machines, but he had developed a close friendship with Hendee and Hedstrom and in 1909 Crocker left Thor to join Indian. He was sent to San Francisco to handle the parts department in the factory headed by “Hop” Hopkins.

In 1912 Crocker’s personal life was “deeply affected” by the death of fellow Indian racer Eddie Hasha at the Newark Motordrome (The Wall of Death: A History of the Motordrome and Silodrome); Hasha was competing in a five-mile handicap race against five other riders, including world record holder Ray Seymour. While leading in the third lap Hasha’s motorcycle began to misfire. He was overtaken by Seymour as he reached down to make an adjustment, and when he accelerated to close on Seymour at 92 miles per hour (148 km/h) Hasha’s motorcycle suddenly turned sharply into the rail surrounding the track. The bike rode the rail for some 100 feet (30 m), decapitating a bystander who had put his head over the rail to watch the race. The machine then struck a large post: Hasha flew out of the racing area into the grandstands and was killed instantly along with three young boys and another bystander.

In 1912 Crocker’s personal life was “deeply affected” by the death of fellow Indian racer Eddie Hasha at the Newark Motordrome (The Wall of Death: A History of the Motordrome and Silodrome); Hasha was competing in a five-mile handicap race against five other riders, including world record holder Ray Seymour. While leading in the third lap Hasha’s motorcycle began to misfire. He was overtaken by Seymour as he reached down to make an adjustment, and when he accelerated to close on Seymour at 92 miles per hour (148 km/h) Hasha’s motorcycle suddenly turned sharply into the rail surrounding the track. The bike rode the rail for some 100 feet (30 m), decapitating a bystander who had put his head over the rail to watch the race. The machine then struck a large post: Hasha flew out of the racing area into the grandstands and was killed instantly along with three young boys and another bystander.Hasha’s riderless machine dropped back onto the track hitting last-place rider Johnny Albright, another Indian racer. Albright died four hours later without regaining consciousness.

In 1919 Crocker took over the Denver Co. Indian dealership. Hasha’s widow, Gertrude, was working at the dealership at the time and they developed a romantic relationship; Al and Gertrude were married in 1924 and had a son that same year, also named Albert. Crocker took over the Indian dealership in Kansas City that same year, and functioned as a distributor for several Midwest states.

In 1928 Al Crocker bought the Freed Cycle Company in Los Angeles, which allowed him to take over some limited production for Indian; as well as servicing and retailing bikes, he began machining crankpins and other small parts. Crocker hired Paul Bigsby as shop foreman; a racer and engineer in his own right, Bigsby had been one of Crocker’s supervisors in his early career with Indian and they shared a dedication to motorcycle design and racing. (Paul Bigsby was also the inventor of the The Bigsby vibrato tailpiece, a.k.a. the “Whammy bar” as found on modern electric guitars.) One of their first custom products was an overhead conversion kit for 101 Scouts and Chiefs, which was “marketed to great acclaim”.

Throughout the early 20th century, motorcycle racing was mostly conducted on indoor wooden board tracks. Lightweight machines usually based on bicycle frames ripped around these steeply banked tracks at speeds which could surpass 100 miles per hour. It was an extremely dangerous sport, and even though no laws had really been passed to make board racing illegal its popularity had suffered a steady decline ever since Hasha’s disastrous crash back in 1912.

By the early 1930s Flat Track racing was starting to take off, and the sport was dominated by British machines. Crocker and Bigsby went to work designing a Speedway racer to participate in the new competition class. Their new lightweight frame utilized an Indian Scout ‘101’ 45ci. (750cc) V-twin engine which “proved satisfactory”, and in 1932 Crocker started producing OHV conversions for the Indian motor with a bolt-on cylinder and head. These first OHV conversions had a 30ci. (500cc) capacity, and mounted in the Crocker-built speedway frame they out-performed the Rudge engines which were dominant at the time. But the big Indian V-twins, although powerful, still carried too much weight.

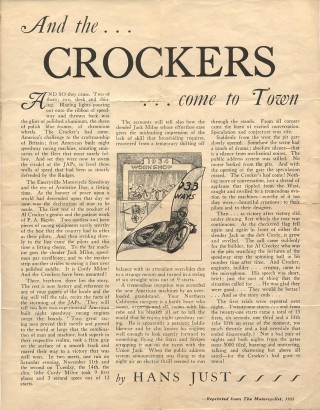

In 1933 Crocker and Bigsby developed a single-cylinder 30.50ci. (500cc.) OHV Speedway racer which brought the weight down considerably; the Crocker Speedway racer first appeared on the Emeryville CA. track on Nov 30, 1933, and won 9 of 12 heats in one evening. The Motorcyclist published a review of the competitions in their December 1933 edition, stating that; “…two spotless and keen pieces of racing equipment surely worthy of the best the country had to offer as their pilots. The first race was ridden by Jack Milne…speedman par excellence…and Cordy Milne….Two American-built night speedway racing engines swept the boards…9 first places and 3 second spots out of 12 starts…The call came suddenly for the builder, for Al Crocker who was in the pits…[He] came to the microphone. His speech was short, brief; just the sort of thing that the situation called for…He was glad that they [the bikes] were good…They would be better.”

In 1933 Crocker and Bigsby developed a single-cylinder 30.50ci. (500cc.) OHV Speedway racer which brought the weight down considerably; the Crocker Speedway racer first appeared on the Emeryville CA. track on Nov 30, 1933, and won 9 of 12 heats in one evening. The Motorcyclist published a review of the competitions in their December 1933 edition, stating that; “…two spotless and keen pieces of racing equipment surely worthy of the best the country had to offer as their pilots. The first race was ridden by Jack Milne…speedman par excellence…and Cordy Milne….Two American-built night speedway racing engines swept the boards…9 first places and 3 second spots out of 12 starts…The call came suddenly for the builder, for Al Crocker who was in the pits…[He] came to the microphone. His speech was short, brief; just the sort of thing that the situation called for…He was glad that they [the bikes] were good…They would be better.”

There is some disagreement on the number of Speedway racer motorcycles developed, but apparently Crocker & Bigsby went on to produce between 30 and 40 bikes in the LA shop; the little company even built a pair of experimental chain-drive, 42hp. OHC engines in 1936 intended to compete with the new JAP Speedway motor (J.A. Prestwich Industries- History of the J.A.P.). But with the growing requirements for power and the number of engine designers entering the racing circuits, the Crocker Speedway engine clearly needed even further developments to remain competitive. Rather than continue with Speedway racing, Al Crocker and Paul Bigsby turned their attention to big V-twins.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 had provided $75 million dollars annually for American road construction and improvement, and a national grid of 20,000 miles worth of interconnected “primary highways” had been built through the 1920s and early ‘30s. This new grid of relatively safe, accessible and practically endless asphalt had spurred a growing demand for high-speed touring bikes. In 1935 Crocker and Bigsby set their sights on a heavyweight, high performance, v-twin motorcycle. It would be called the ‘Crocker’.

The motorcycle design was based on the Indians that Crocker had worked on previously, but the engine was unique. At 3.25” bore to 3.625” stroke, the 61 cubic inch cylinders were almost square and were set 45 degrees apart. Compression was rated at 7:1.

This machine was designed to be with customized: the cylinder walls were cast extra thick to allow for over-boring and the gearbox could withstand 200 horsepower, allowing it to take a real beating without any complaints. Bigsby designed a hemi-head which, once installed on stock 1936 machines, peaked at 60 horsepower and gave the Crocker a 120 mph. top end. Al Crocker was reportedly so confident in the bike that he offered to refund the full purchase price to any buyer who was beaten by a rider on a Harley or an Indian.

In reality, the final result was less than graceful; it ran rough, it was a bitch to start and it was “noisy enough to wake the dead”. But once a Crocker was actually moving there was nothing that could beat it. It became an instant American classic; Harley-Davidson and Indian got caught with their pants down, and even their modified bikes couldn’t come close to the stock performance of a Crocker.

The bikes used HD valve gears, Indian timing gears and brake shoes, and HD or Indian headlamps. Most ancillary parts came from standard industry suppliers; stock Autolite electrics, Linker carbs, Messinger saddles, Splitdorf magnetos and Kelsey Hayes rims. The main bits were made in Crocker’s own facility, with each bike built to the customers’ specifications for tuning and engine displacement.

Engines typically ranged around 1000cc, but in the most extreme case reached 1490cc. The ‘typical’ 62ci. Big Twin produced 55-60hp, exceeding the sidevalve Indian and HD models by 50%. Harley Davidson introduced their first OHV V-twin EL ‘Knucklehead’ 6 months after the Crocker, but was 15mph slower. Harley-Davidson was rumored to be so embarrassed by the introduction of the Crocker V-Twin that they threatened to boycott manufacturers that supplied parts to Crocker’s plant. In fact, Crocker instructed their customers to buy certain replacement parts from Harley, and that action was probably not taken unilaterally: at the very least it certainly resembles appeasement. Harley-Davidson did threaten legal action for patent infringement, but the case was thrown out.

1939 Crocker Special

The apparent weakness in Crocker’s strategy was that his small company could not hope to compete with the price of mass-produced Indians and Harleys. Crockers sold for 25-50% more than their competition, which prevented much of a dealer markup. Nonetheless, during the mid to late 30’s Crocker Motorcycle Company had at least five “dealerships”. Mickey and Johnny Colavito ran a Crocker dealership in Newark, New Jersey from 1936 to 1939; the Colavito brother’s shop sold both the speedway single dirt track and V Twin street bikes, and ran a Crocker speedway single successfully at the “Cinder Block Track” in Newark on Saturday nights. George Beerup was a known Crocker Motorcycle dealer in the Los Angeles area from 1936 to 1939, and usually had a Crocker V twin sitting on the sidewalk in front of his shop or occasionally displayed in a window. “Bill” Clymer, Floyd’s brother, also had a Crocker dealership at 933 East Anaheim Street in Long Beach, California and “Johnson Motors” was a Crocker dealer in Pasadena. Another exclusive Crocker dealer was “The Motorcycle Store” located at 993 Franklin Street in Johnstown PA, owned by Joseph Zanghi. Because so many Crocker’s were found in the Chicago area it is thought that there must have been a dealer there as well.

To give the Crockers an extended range, the size of the cast-aluminum fuel tanks was enlarged in 1938; all earlier models are referred to as ‘Small Tanks’, and later models ‘Big Tanks’. Crocker continued to develop the motorcycles through a limited production of app. 72 total V-twins, but the intervention of WWII eventually did what Harley couldn’t. Crocker was unable to purchase parts, and without facilities for mass production the little company had no chance for military contracts.

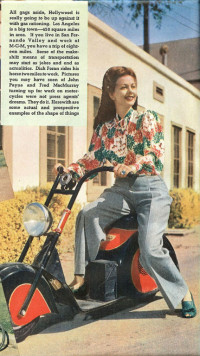

Just prior to the war Crocker also tried to market a small Vespa type scooter called the Crocker “Scootabout”, using a small Lawson air-cooled engine.

The “Scootabout” was considered a forerunner at the time it was released. Scooters of the time were very plain, no nonsense fun machines, Crocker gave them style with a streamlined design including two-toned paint jobs and skirted fenders even before Indian made that look famous, and the company furthered scooter design by adding a crude suspension to the front end in 1941. The “Scootabout” sold for $139.00: it is thought that less than 100 of these little scooters were ever produced.

The “Scootabout” was considered a forerunner at the time it was released. Scooters of the time were very plain, no nonsense fun machines, Crocker gave them style with a streamlined design including two-toned paint jobs and skirted fenders even before Indian made that look famous, and the company furthered scooter design by adding a crude suspension to the front end in 1941. The “Scootabout” sold for $139.00: it is thought that less than 100 of these little scooters were ever produced.

By 1942 “war work” restrictions meant Crocker could no longer produce any motorcycles, and the Crocker Motorcycle Company was effectively finished. Even without the war, there was no way Crocker could have survived the competition form Harley and Indian much longer. After the demise of the Crocker Motorcycle Company, Al Crocker, along with his son Albert, went on to manufacture war-related machinery and aviation parts for the Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica, California; the remaining inventory of the Crocker Motorcycle Company was sold to ex-employee Elmo Looper, who was a member of the 13 Rebels Motorcycle Club (13 RMC) of Southern California.

Al Crocker died at his home in South Pasadena in 1961 at the age of 73.

Paul Bigsby went on to found Bigsby Guitars, selling his designs to Gibson, and other guitar companies.

In 1997 the Crocker name was resurrected by collectors Markus Karalash and Michael Schacht in order to supply replacement parts for the original Crockers. After an enthusiastic response to reproduction parts produced for a restoration, the partners decided to officially incorporate Crocker Motorcycle Company in January 1999. In 2002 steps began to trademark Crocker Motorcycle Company Worldwide, and they anticipate the ability to eventually assemble complete reproductions of all Crocker Motorcycles.

“Crocker Motorcycle Company produces parts that are exactly as the originals by incorporating “old school” pattern making methods with ultra modern measuring and machining technology. We use CMM (computer coordinate measuring) and in many cases CNC machining techniques to ensure the exactness of each part we make. Our patterns are made by old world craftsmen who have a dedication to making things correctly, rather then quickly. To ensure a strict quality control, we have created an extensive library of Cad-Cam engineering drawings for every part we produce.”

References:

The History of the Thor Motorcycle Company by Greg Walter

Crocker Motorcycle Company (official site)

Extract of Albert Crocker obituary by Floyd Clymer, Cycle magazine (Yahoo Groups post)

The Crocker Story (The Vintagent)

Al Crocker and the Crocker Motorcycle Company – TheWorldOfMotorcycles.com